The Universal Basic Income – A New Tool for Development Policy? report by Johanna Perkiö (University of Tampere/BIEN Finland) is now available online. Download the full report here.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. Introduction

2. The many faces of cash transfers

3. Experiences of basic income: case studies in Namibia, India and Brazil

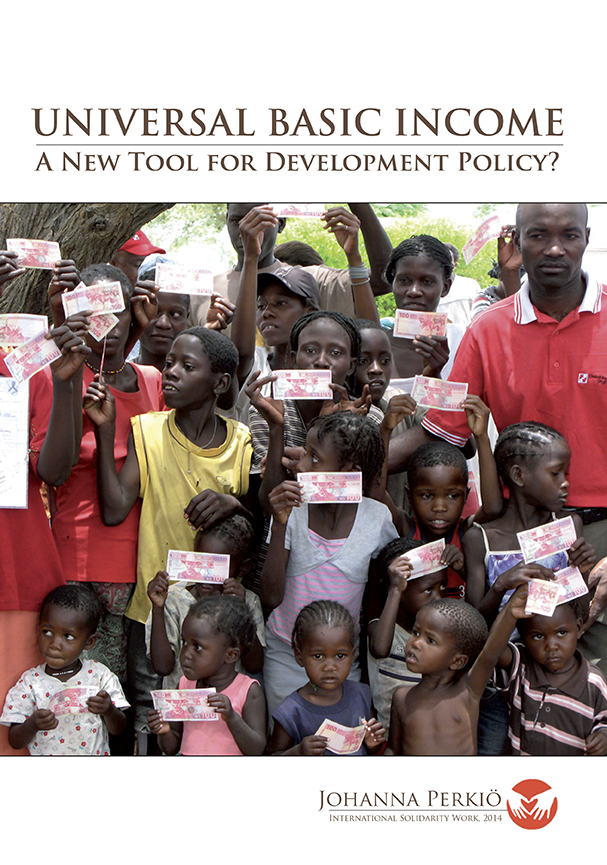

3.1 Namibia: the BIG experiment in the Otjivero-Omitara village

3.2 India: Three Projects Piloting the Unconditional Cash Transfer

3.3 Brazil: from Bolsa Família to Citizen’s Basic Income?

4. Towards Universal Social Protection

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, social protection has risen high on the international policy agenda. It is becoming increasingly acknowledged that economic growth and conventional development policy measures alone are insufficient to combat poverty as far as the unjust economic structures remain in place.

Deepening inequality and slowly growing employment rates(1) accompanying rapid economic growth has led many countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America to tackle poverty directly by establishing social protection systems for their citizens. The remarkable progress in the social policy field has drawn enormous international attention and brought about the new global policy approach of Social Protection Floor (SPF) which was in 2012 endorsed by the ILO and other UN agencies, various NGOs, G20 and the World Bank. The Social Protection Floor initiative is an integrated set of recommendations for countries to guarantee income security and access to essential health care and social services for all their people across the life cycle. It emphasizes the need to implement comprehensive, coherent and coordinated social protection policies and seeks to re-establish the case for universalism within a development context.(2)

The Social Protection Floor is a broad policy framework that does not include recommendations on any particular measures to achieve its goals. Regarding income security, the measures currently in place vary from universal pensions or means-tested family and child assistance to guaranteed employment programs. Many of the new policies have taken the form of direct cash transfers, which have proved to be more cost-efficient and effective in reducing poverty than conventional forms of aid such as food aid or vouchers(3). In addition, they avoid the harmful effects on local markets and agriculture. Most of the newly implemented cash transfer programs are targeted only at the poor and often are conditioned on the recipient’s conduct.

Some of the social policy experts have come to argue that the social protection models based on outdated economic and labour market structures are not the most relevant in the post-industrial era(4), when the forms of employment, as well as lifestyles and family patterns, are becoming increasingly fluid and flexible. In this context, the idea of universal basic income has been brought up as a new alternative approach to social policy. Basic income as such is not a new idea, but it is becoming increasingly recognised as a promising alternative to the highly bureaucratic and complicated systems of targeted and conditional social security. The idea of basic income is to guarantee a certain minimum income to all members of society as a right without means-test or conditions. It provides each individual regularly with a determined sum of money, which is granted regardless of the recipient’s employment status, family relations or socio-economic position.(5) In most proposals, the basic income grant itself is tax-free, but all earned income above it are taxed either on progressive or flat-rate scale. Through income taxation, the government can charge back the equivalent of the given grant from higher earning individuals who do not need the income supplement. Few pilot projects of basic income with encouraging results in terms of reduction of poverty, improving health and nutrition and boosting economic activity have been carried out in Namibia, India and Brazil.

This report examines the potentials of basic income to serve as a new tool for social and development policy, drawing from the recent experiences from the pilot projects. The structure of the report is as follows: Chapter two provides a brief literature review of cash transfer policies currently in place in many developing countries and assesses the potential advantages of universal and unconditional transfers over targeted and conditional ones. Chapter three presents the three country cases where universal cash transfer policies have been tested or gradually implemented. Chapter four concludes and explores the prospects of basic income as a part of the new development policy agenda. The empirical material regarding basic income experiments is collected from the projects’ own research reports and newsletters, as well as relevant academic and non-academic articles.

The cash transfer schemes piloted in Namibia and India correspond to the ‘standard’ definition of basic income: the transfers were given to all residents of the selected area (in Namibia the recipients of the universal state pension were excluded) without any conditions regarding the recipients’ conduct, social status or use of the money.

In India the pilot scheme was called Unconditional Cash Transfer and in Namibia the Basic Income Grant (BIG). Brazil’s case differs from India and Namibia in that there has been only a minor NGO-run pilot project, in which the data has been collected less systematic, but Brazil as a whole and some municipalities have taken steps toward implementing a scheme called Citizen’s Basic Income.

In this report, basic income is examined as an alternative to conditional and targeted minimum income schemes. The contributory social insurance systems (e.g. earnings-related unemployment benefits or pensions) still hold their place as an additional system to minimum income guarantee. Basic income is not regarded as an alternative, but as a complement, to comprehensive social and health care services, education and employment generating policies.

1. Income and wealth inequalities have increased in most countries, as have inequalities based on gender, ethnicity and region. Between 1990 and 2000 ”more than two-thirds of the 85 countries for which data are available experienced an increase in income inequality, as measured by the Gini index” (ILO 2008, cited by UNRISD 2010, 65). Though employment is often treated as an automatic by-product of growth, in reality employment growth has often lagged behind GDP growth as a result of orthodox macroeconomic policies and technological development, which has led re-searchers to talk about ”job poor” or ”jobless” growth. Evenwhen employment is available, the vast majority of wage earners in poor countries do not earn enough to lift themselves from poverty (UNRISD 2010).

2. Deacon 2013; ILO/WHO 2011.

3. Hanlon et al. 2010; Standing 2012b, 28–34.

4. Most of the so-called developing countries are classified as pre-industrial countries. However, the problems of income insecurity are even greater in those countries, and it seems unlikely that their labour market will ever become corresponding to the western industrial era.